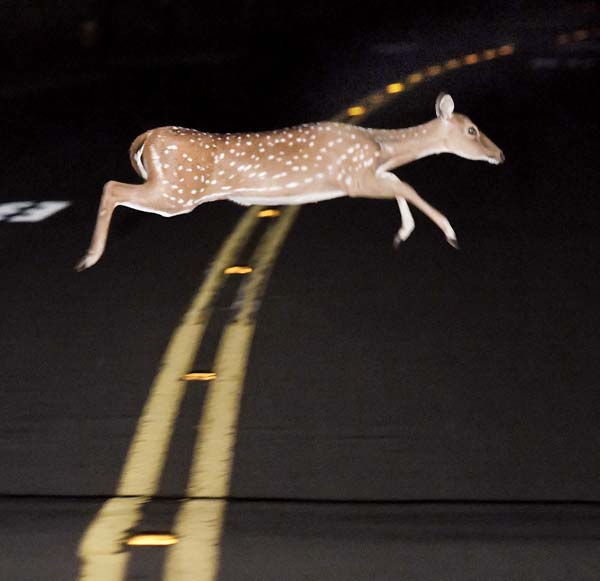

DLNR official: Deer may be declining amid control hunting, ‘but it’s not enough’

OLINDA — Longtime farmer, producer and wildlife manager Michael Crowder, who’s also the president of the National Association of Conservation Districts, was “really shocked” to learn how bad the axis deer situation is in Maui County.

Having worked with communities along the U.S. West Coast and all the way out to Palau and the Virgin Islands, Crowder said last week at the Oskie Rice Clubhouse that “we have to come together as a partnership with Hawaii and the county to make sure to find a solution that really works.”

Experts and advocates from NACD, which provides a voice for more than 3,000 conservation districts across the United States, were in town for a collaborative Pacific regional conference last week and met several of Maui County’s farmers, ranchers, producers and business owners to discuss environmental and natural resources, policy and legislation, climate change, and conservation work.

NACD members and attendees took tours through areas like Haleakala Ranch and the University of Hawaii’s Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources experiment station in Piiholo, as well as heard updates from local farmers, the state Department of Land and Natural Resources and the Maui Axis Deer Task Force.

Mayor Michael Victorino also met with the team last week to discuss the administration’s top concerns, such as infrastructure, axis deer and feral pigs, Crowder said.

“Coming from eastern Washington state, I can tell you that I’m used to living in the desert, but I did not realize how dry it would be in this area,” Crowder added. “I understand that there is more rain in the mountains, but I didn’t understand that it would be quite this dry. It really is a longer-term drought that affects the habitat, the grasses and the vegetation, and so that was something that I wasn’t expecting.”

Drought, coupled with “severe overpopulation” of axis deer, is creating extreme challenges with producing healthy crops, having enough feed for livestock, mitigating erosion and growing native plants, he said.

It’s also not healthy and humane for deer populations to get so large to the extent that animals are starving and scavenging for food, he noted.

“Right now we’re in serious drought, which is out of our control, so we’ve been taking proactive approaches at destocking cattle but it’s a constant battle with deer right behind or right in front of them, so our feed source is low,” said Wendy Rice Peterson of Kaonoulu Ranch, adding that they’ve been doing professional harvesting of deer and installing fencing. “I think we have to come up with a solution for the deer problem on the island.”

Makawao resident Jeff Bagshaw from DLNR’s Division of Forestry and Wildlife said that current population estimates count between 60,000 to 65,000 deer, which is down from last year’s 70,000 due to control hunting programs.

But, it’s not enough,” Bagshaw said Thursday during a presentation at Oskie Rice. “If we did nothing, that would balloon up.”

About 94 percent of newborns make it through their first year in Hawaii because there are no natural predators besides humans. In their native lands, about 64 percent do not live through their first year.

“There’s problem one,” he said. “Here on Maui, we also think that the population is 10 percent male, so why did the deer suddenly explode? Well, it’s just math. They can give birth at nine months, so one doe … if a hunter says ‘oh Jane doe right there, I’m going to save her for the next generation,’ Jane doe in her 10- to 15-year lifetime can produce about 100,000 females if you extrapolate out her daughter’s granddaughters, great-granddaughters, great-great-granddaughters in 10 years. That’s where our population problem comes from.”

It’s not just about food security, he added, it’s about water security and soil conservation. He said it should be everyone’s responsibility, from government leaders to landowners to small hunters, to help mitigate the “deer apocalypse” with controlled hunting, fencing and reporting.

The DLNR only manages about 20 percent of the land on Maui — the remaining 80 percent is privately owned.

Kyle Caires, animal scientist and Maui County livestock extension agent with the University of Hawaii’s College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources, said that deer have already found their way deep into the Kahakuloa watershed, out in Hana and by the Waihee Ridge Trail.

“The deeper the axis deer get, the harder it’s going to be, but there is no silver bullet to this problem,” Caires said during his presentation. “It requires an integrative approach, fencing, hunting, depopulation, and frankly, a statewide management plan is definitely needed. … We need to take advantage of the relationships that comes from having all of you come to Maui, sharing your mana’o — share your knowledge with us — and help us link better with legislators, policy makers.”

To keep the number of axis deer in control, about 20,000 need to be culled per year, said Maui County Council Member Yuki Lei Sugimura, who represents the Upcountry district and launched the 30-member Axis Deer Task Force a year ago.

Haleakala Ranch Land Manager Jordan Jokiel said some of the more challenging things to get federal funding or grants for are production work and perimeter fences through the Natural Resources Conservation Service.

To help with this, Sugimura said that Lokahi Pacific has been accepting grant applications for a $1.5 million assistance program to help with crop damage, fencing costs and other impacts from axis deer and feral animals — 40 applicants have received $30,000 grants so far since the Aug. 15 deadline.

Also, the Inflation Reduction Act includes around $1 billion for conservation technical assistance, which allows NRCS and conservation districts across the country to support producers, according to NACD. This “large climate, tax and health care-focused” bill also provides $18 billion for voluntary conservation programs administered by the United States Department of Agriculture’s NRCS between fiscal years 2023 and 2027.

There have to be public and private partnerships to help with drought and feral ungulate control on Maui, Molokai and Lanai, and “think outside the box,” said Crowder.

See article at Maui News HERE.